Serverless Scheduler

11 Oct 2019Update: In November 2022 AWS has released the EventBridge Scheduler. It does what I expect from a serverless scheduler, and has a free tier of 14 million invocations per month. Therefore, I’m deprecating this project.

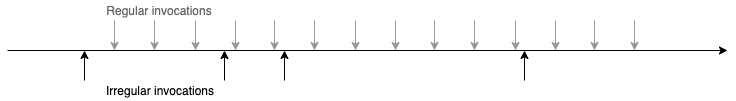

AWS offers many great services, but when it comes to ad hoc scheduling there is still potential. We use the term ad hoc scheduling for irregular point in time invocations, e.g. one in 32 hours and another one in 4 days.

Zac Charles has shown a couple ways to do serverless scheduling, each with their own drawbacks in terms of cost, accuracy or time in the future.

In Yan Cui’s analysis of step functions as an ad hoc scheduling mechanism he lists three major criteria:

-

Precision: how close to my scheduled time is the task executed? The closer, the better.

-

Scale — number of open tasks: can the solution scale to support many open tasks. I.e. tasks that are scheduled but not yet executed.

-

Scale — hotspots: can the solution scale to execute many tasks around the same time? E.g. millions of people set a timer to remind themselves to watch the Superbowl, so all the timers fire within close proximity to kickoff time.

This article shows my serverless scheduler and how it performs against these criteria. Follow-up articles will take a closer look at scaling and cost.

Overview

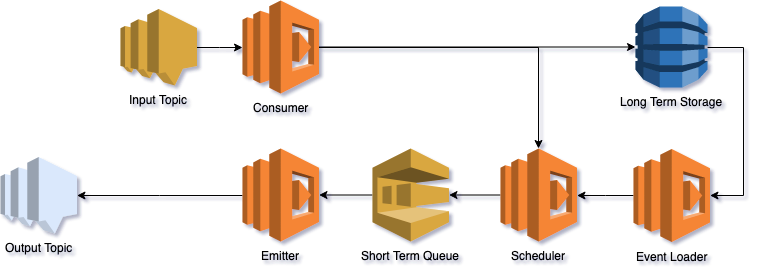

The service’s two interfaces are an SNS input topic which receives events to be scheduled and an output topic which is hosted by the consuming account.

Each input event must contain an ARN to the SNS output topic where the payload will be published to once the scheduled time arrives.

Internally the service uses a DynamoDB table to store long term events. Events whose scheduled time is less than ten minutes away are directly put into the short term queue.

This queue uses the DelaySeconds attribute to let the message become visible at the right time. The event loader function is basically a cron job. The emitter function finally publishes the events to the desired topics.

Usage

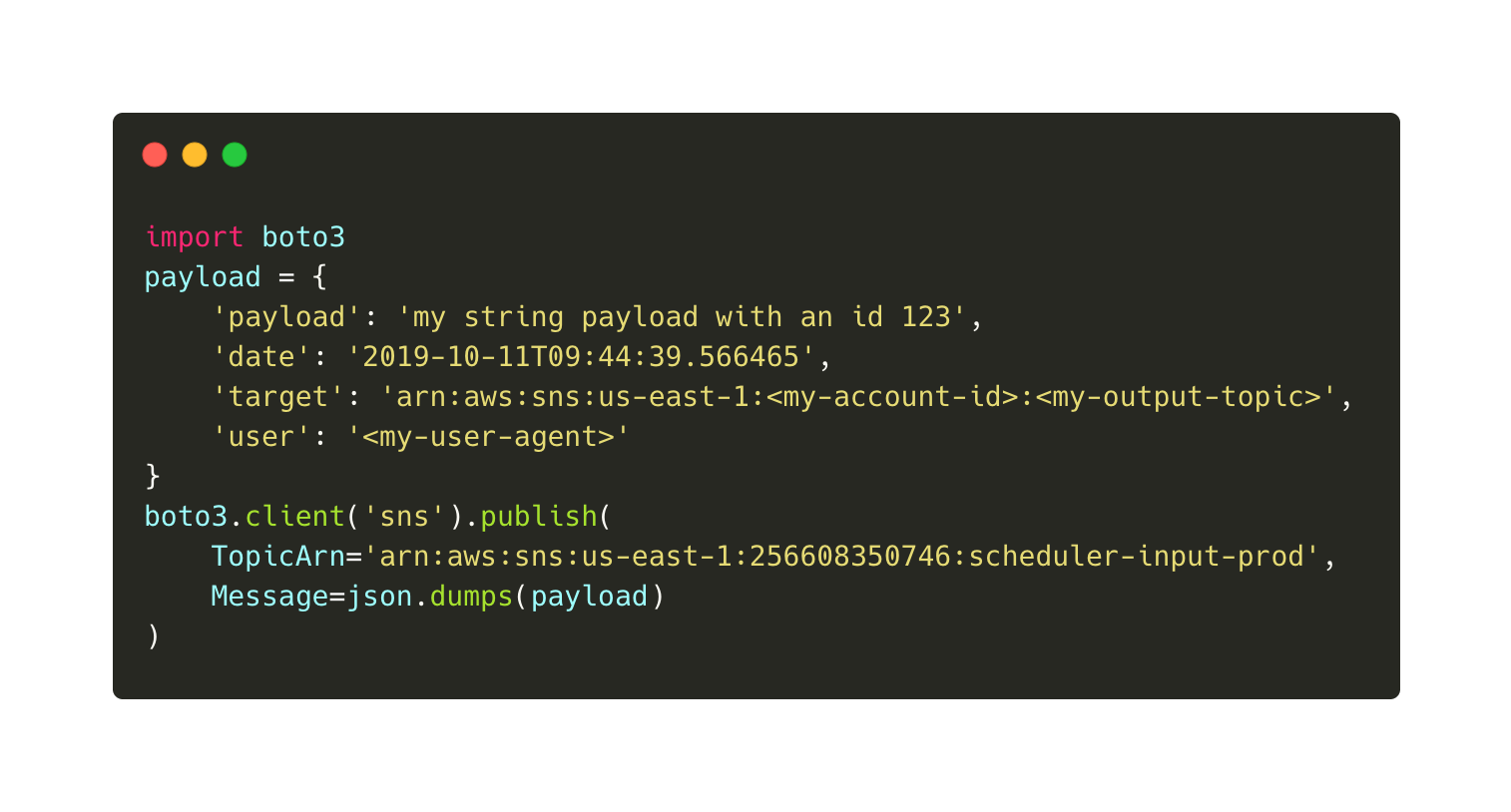

The scheduling service takes an event with a string payload along with a target topic, the scheduled time of execution and a user agent. The latter is mainly to identify callers.

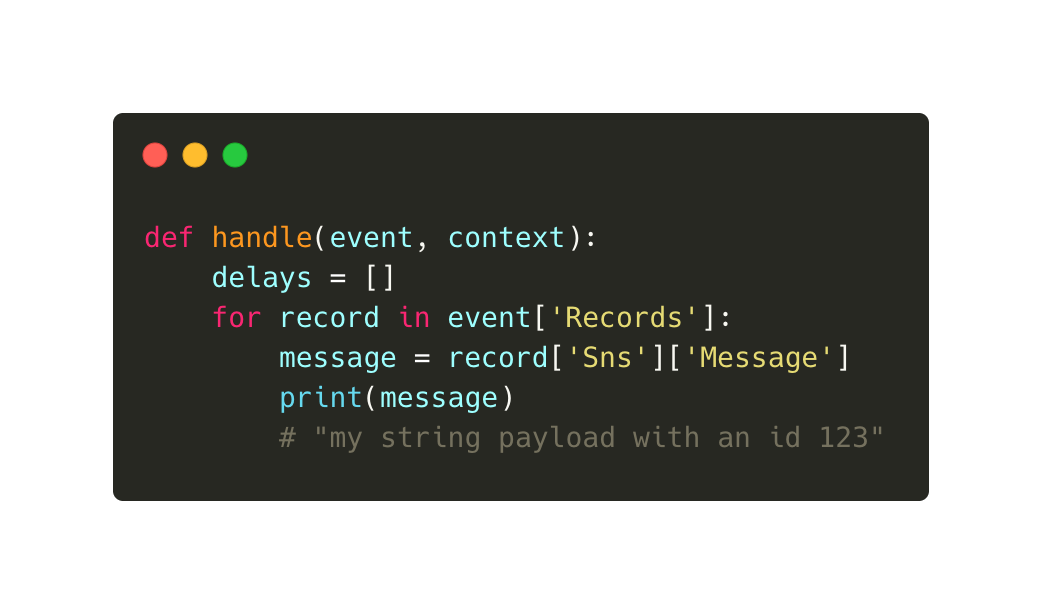

The above python code publishes an event with a custom string payload. Please make sure that you fill out all four fields or the event may be dropped. See more in the Troubleshooting section at the end of the article.

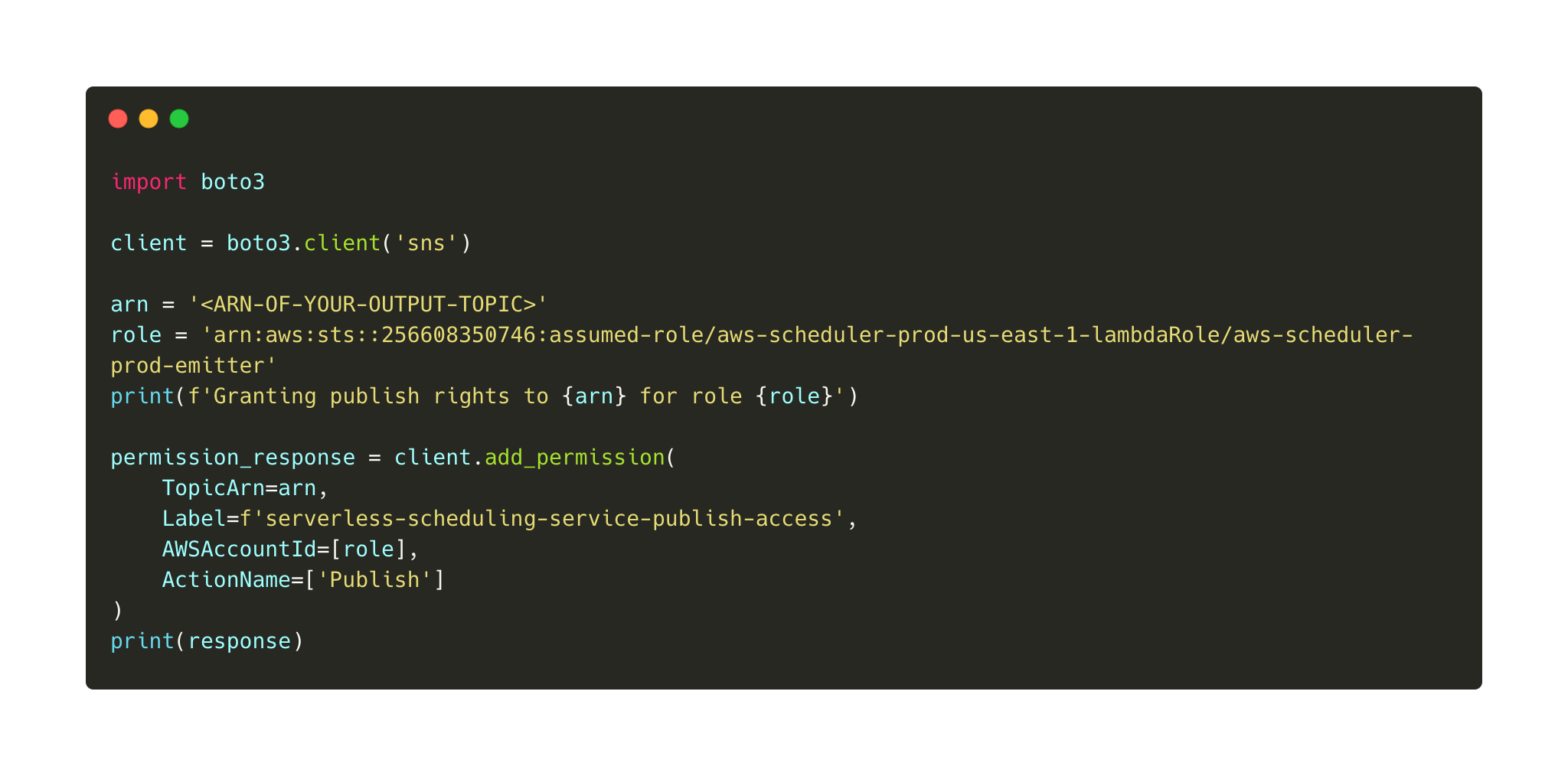

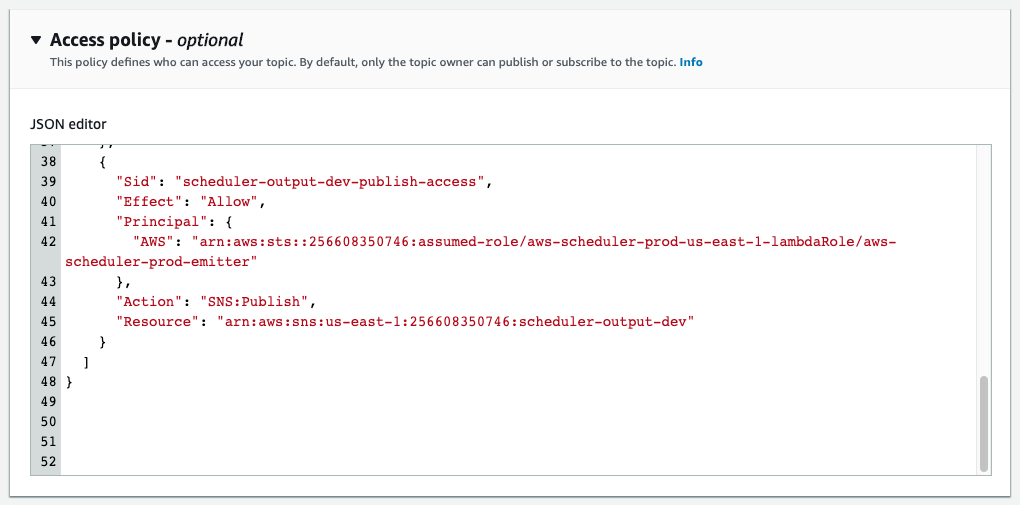

Note that we have to create our own SNS topic which must grant publish rights to the serverless scheduler. The quickstart project contains a script that helps you with creating the SNS topic. The AWS role of the public serverless scheduler is arn:aws:sts::256608350746:assumed-role/aws-scheduler-prod-us-east-1-lambdaRole/aws-scheduler-prod-emitter

You may also manually assign an additional access policy to your SNS topic.

After that you need a lambda function that consumes events from your output topic.

That’s it. You can use the quickstart project to quickly schedule and receive your first events. Go try it out!

Evaluation

Let’s come back to the criteria mentioned in the intro: Precision, Scale and Hotspots.

Precision

Precision is probably the most important of all. Not many use cases are tolerant to events arriving minutes to hours late. A sub second delay however is viable for most use cases.

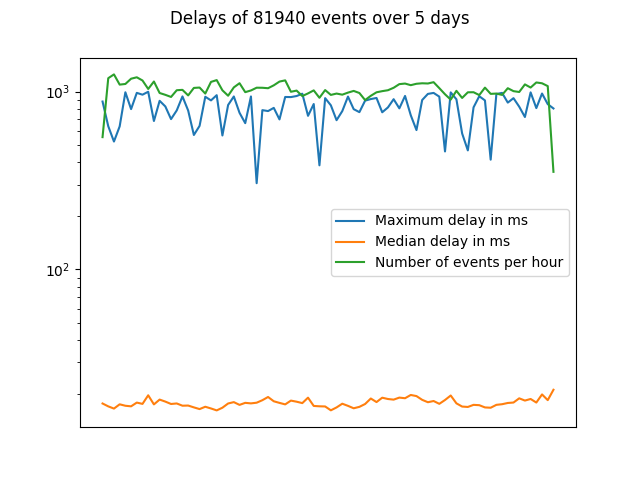

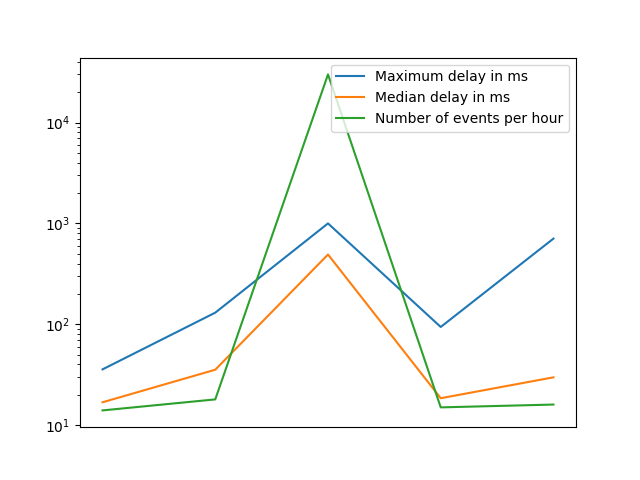

Over the last five days I create a base load of roughly 1000 events per hour. The emitter function logs the target timestamp and the current timestamp which are then compared to calculate the delay. Plotting this data gives us the graph below.

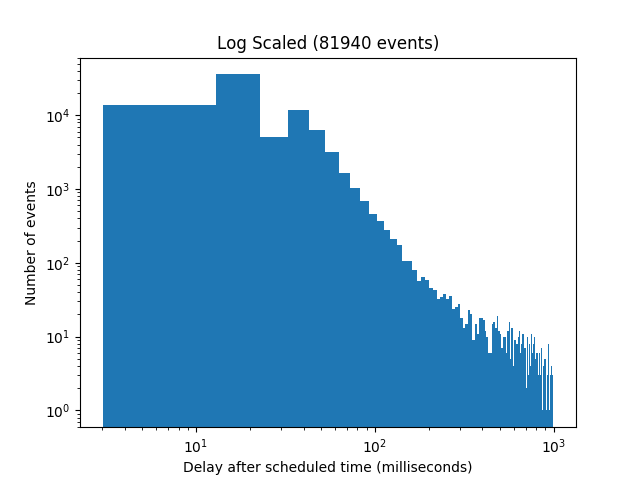

As you can see, the vast majority is well below 100 ms with the maximum getting close to 1000 ms. This gets clearer when you take a look at the histogram.

Scale

Scaling for many open tasks is an easy one here. SQS and DynamoDB don’t put a hard limit on how many items you can process. Therefore the serverless scheduler can hold millions and billions of events in storage for later processing.

The precision shouldn't be affected by the queue depth or the enqueue rate. It's more affected by the ability of the consumers to pull the data out. Once the data is enqueued, and it's timestamp (+ delay) is greater than the current timestamp, the message becomes available.

— Daniel Vassallo (@dvassallo) October 10, 2019

Based on a discussion with Daniel Vassallo I don’t believe SQS to become a bottleneck.

The only bottleneck is the event loader function. It does however use a dedicated index which helps to identify which items are soon to be scheduled. It then only loads the database IDs and hands them over to a scalable lambda function which then loads the whole event into the short term queue.

Tests with varying loads showed that the bottleneck lambda function is able to process more than 100.000 events every minute or 4.3 billion events per month. Due to increased costs I did not run tests at higher scales. Contributions are welcome ;)

Hotspots

Hotspots can arise when a lot of events arrive at the input topic or are to be emitted within a very short time.

DynamoDB is configured to use pay-per-request which should allow for nearly unlimited throughput spikes, however I had to add a retry mechanism when DynamoDB does internal auto scaling. The most time critical function, the emitter, does any possible database operations after emitting the events to the output topic.

Both the SNS input topic and the SQS short term queue are not expected to become slow under high pressure, but the consuming lambdas could.

So, Lambda might add some delays there. It doesn't scale up instantly, so if your queue were to receive a big burst of messages, it could take a few minutes for Lambda to ramp up its polling frequency. This behavior is described here in detail: https://t.co/4rCJGtxOvy pic.twitter.com/0oeQiLuGLt

— Daniel Vassallo (@dvassallo) October 10, 2019

Randall Hunt wrote an AWS blog article which takes a deep dive on concurrency and automatic scaling in this situation.

[…] the Lambda service will begin polling the SQS queue using five parallel long-polling connections. The Lambda service monitors the number of inflight messages, and when it detects that this number is trending up, it will increase the polling frequency by 20 ReceiveMessage requests per minute and the function concurrency by 60 calls per minute.

While cold starts of lambda functions can result in a slight increase of delays, the polling behaviour or an eventual lambda concurrency limit could lead to major delays.

To test this I scheduled 30.000 events to be published within a couple seconds. While the median went well up (probably due to cold starts), this was still not enough to hit any limits.

To sum up the Hotspots section: Very sharp spikes with very high loads can become an issue, but those are so big I couldn’t test them yet.

I’m curious about an upcoming talk at re:Invent 2019 which takes a deep dive into SQS.

If you are interested in the integration of SQS and AWS Lambda, this session at AWS re:Invent 2019 looks to get pretty deep:

— Eric Hammond (@esh) October 11, 2019

API304 - "Scalable serverless architectures using event-driven design"

Recordings should be available on YouTube afterwards.https://t.co/pPpYf339dN

Troubleshooting and Error Handling

Due to the asynchronous nature of the service, error handling is a bit trickier. I decided against an API Gateway endpoint to publish events due to its cost of 3.5$ per million events (compared to SNS’ 0.5$ per million events). Errors can be published to another output topic, the failure topic.

If the event is not published at your output topic, please first make sure you pushed a correct event to the input topic. It must contain all of the four fields payload, date, target and user. All of those must be strings.

You may additionally add a field failure_topic to the event which contains the ARN of another SNS topic where you’d like to be informed about errors. Note that this must have the same publish permission for the serverless scheduler as your output topic does.

Conclusion

The serverless scheduler appears to perform excellent both in precision and scale. Hotspots might become an issue at very sharp spikes and exceptional volume, but the actual limits remain to be discovered.

I’d be happy to see your testing results and what you think about the serverless scheduler. Go try it out with the quickstart project or check out the source code. Would you attach it to your own project?

More tests and insights will be published over the next weeks.

Enjoyed this article? I publish a new article every month. Connect with me on Twitter and sign up for new articles to your inbox!